Gemma Peacocke is the recipient of this year's SOUNZ Commission for Orchestra and Sistema Youth Orchestra. Her new piece Manta premieres this Saturday 7 October at the Michael Fowler Centre by Arohanui Strings and Orchestra Wellington.

SOUNZ had the opportunity to find out more about Gemma's experience with writing this exciting commission.

Can you tell us about the inspiration behind your composition, Manta, and how you envisioned it resonating with the children's string orchestra?

I first saw manta rays in Wellington harbour skating across the seafloor at Oriental Bay. I was taken aback by their sheer size, and even though someone told me that they’re harmless, I did not want to be in the water with them. Later, in Hawaii, I got to see them gliding and somersaulting at night and I found myself in awe. In Māori mythology, whai are often portrayed as kaitiaki, and in writing Manta, I was inspired by Wiremu Grace’s story Whaitere about an enchanted stingray who visits her parents in the underworld before returning as a kaitiaki of the sea. I think children, like adults, are moved by mythic stories about journeys and of seemingly monstrous beings turning out to be rescuers and protectors.

You are currently based in Brooklyn, New York, and have been able to come back to New Zealand to work on this project. How is life as a composer there, and how has it influenced your development?

I was living in Brooklyn when the pandemic hit in March 2020. There were sirens all day and all night. It was difficult to imagine all these people getting so sick in their apartments somewhere close by, but unseen by us, and we could only hear the devastating result of the early virus. With the closure of schools and workplaces, people began to let off fireworks all day and night. The pharmacies were cleared out and basic supplies were hard to find, and there was a feeling of desperation. Then the president started talking about closing down the borders, so we packed our bags and flew back to New Zealand for a few weeks. A few weeks turned into a year and a half, and when we finally went back to New York, the neighbourhood had been wrecked with the virus and with the closure of most of the businesses around us. There was a lot more drug use and street homelessness, and the city’s venues were still not really programming seasons. Last year we decided to move back out to Princeton where I’m finishing a PhD in composition and interdisciplinary humanities, and my daughter was born here in January.

I’m figuring out how to balance being a parent and an artist (as well as a teacher and someone who occasionally likes to eat food and stare at a television screen). I commute into the city once a week to teach at NYU and I like having the connection to the chaos and culture of New York while having a quiet respite in leafy, suburban New Jersey! The years I spent in New York changed my approach to my career as a composer. I became a fundraiser, producer, grant writer, and a faster, less self-critical composer. You really have to grind in New York to make things happen, but you can also find highly-talented, hard-working, and driven people who might be willing to share in your vision.

You have had the chance to work on Manta with Arohanui Strings, can you tell us a bit about that experience?

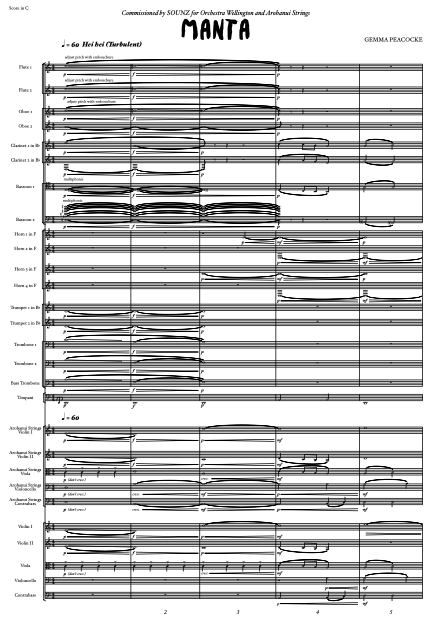

I was lucky enough to attend one early rehearsal and to see how much work the students and their teachers were putting into learning the piece. It’s only five minutes in duration, but it has a lot of notes, and I tried to keep the technical side of the piece not too strenuous but challenging enough to be interesting.

When composing for Arohanui Strings and Orchestra Wellington simultaneously, how did you approach the integration of these two groups in the same score? Were there any specific challenges or opportunities that arose from this collaboration?

Originally I had planned to centre Arohanui Strings as the core of the sound but after talking to Orchestra Wellington and Arohanui Strings, two things became clear: for the kids, sitting alongside the professionals can be fantastically fun and also formative, and the sound that smaller bodies and smaller instruments make is much quieter than the bigger, adult orchestra. I grew up playing the violin and I tried to think about all the things that I liked doing when I was learning, like open string double stops (where you play two strings at the same time). I also wrote in a solo for the concert master that has many of the same features so that Arohanui Strings could have a musical conversation without being overpowered by the entire first violin section.

What has been the most rewarding aspect of collaborating with Arohanui Strings on this project? And what does it mean to you to be able to work with a group like Arohanui Strings?

There’s something deeply moving about people putting so much time into learning how to play your music, perhaps especially when they’re not professional musicians, and it’s a huge honour to be able to work with young people. I loved playing in youth orchestras when I was a kid and I’m deeply appreciative of the opportunity to write for children for the first time in my life. Aotearoa needs more avenues for music education and for children to have access to instruments and teachers. Everyone should be able to participate in making music.

What do you hope the young performers will take away from this concert experience?

I hope that the performers enjoy being onstage alongside the professional musicians and that they feel a strong sense of accomplishment after all the work they’ve put into learning Manta. I also hope that some of them will want to write their own pieces and compose music for Arohanui Strings too!