In his oft-quoted 1946 lecture, “In Search of Tradition”, Douglas Lilburn, the so-called “grandfather” of New Zealand music, turned to New Zealand’s natural landscape as a spiritual and aesthetic foundation for a new national musical tradition. Our unique geographies, he argued, might “impress themselves on our minds” to create a “living tradition”, a musical language sprung forth from the natural environment like a tree sprouting on a hillside.[i]

That same year, Lilburn would attempt to bring this ecologically inflected national style to fruition in his A Song of Islands, a meandering orchestral chorale designed to evoke “the strangeness and remoteness of the islands, and their elemental ambience of oceans and mountains”.[ii] This pastoral soundscape, Lilburn believed, would immediately call to mind the “inherited memory of the primordial voyage, shared by all New Zealanders”.[iii]

Lilburn: A Song of Islands, Performed in 1946 by NZBCSO, conducted by James Robertson.

Of course, Lilburn’s notion of a “shared voyage” – made sonorous through a national musical tradition rooted in New Zealand’s distinct natural environment – is an unadulterated myth. There is no voyage “shared by all New Zealanders”, just as the cultural experience of the New Zealand landscape is far from homogenous. While Māori arrived in Aotearoa by waka in the fourteenth century, nurturing the whenua according to the shared ethos of kaitiakitanga, Pākehā arrived at the height of the European Enlightenment and proceeded to decimate the natural landscape through a rapid process of hyper-industrialised colonisation.[iv]

Two waves of migration, two radically different orientations to the natural landscape – indigenous guardianship, on the one hand, and colonial exploitation, on the other.

Lilburn’s writings – with their sweeping generalisations about a “living tradition” grounded in a shared relationship to the ecological milieu – inadvertently underscore the impossibility of reconciling these two culturally and historically distinct experiences of the New Zealand landscape into a unified national musical style. For how can a composer even begin to musically express the horrific atrocities perpetuated under British colonialism and the terrible ruination inflicted upon the tangata whenua and the land that they nurtured and preserved?

Lilburn, for his part, chose reticence, erasing such cultural tensions from his musical universe. Lilburn was writing at a time when New Zealand was eagerly attempting to refashion itself as a colonial paradise, emboldened by the rapid growth of meat exports to Britain (this era has been described by historian James Belich as the age of “recolonisation”).[v] Thus, rather than addressing the cultural and environmental destruction wrought by British colonisation, he instead opted for a musical language that presents a “young, crude” natural landscape, untouched by human hands but ripe for creative exploitation.[vi]

He adopted a rugged musical pastoralism, flaunting the lofty influence of William Walton, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Frederick Delius, and Jean Sibelius. This pastoral idiom, so clearly inflected by European musical conventions, conspired to paint the New Zealand landscape as a slightly rough-and-tumble cousin to the bucolic European countryside – an arcadian colonial frontier mirroring the aesthetic ideals of the metropole.[vii]

Notably, Lilburn’s pastoral aesthetics obscure the means through which British colonialism transformed the New Zealand landscape. The colonisation of Aotearoa was enabled by two broad scientific and technological shifts: firstly, the Enlightenment, which brought new developments in navigation, cartography, astronomy, surveying, the natural sciences, and ship-building, allowing for James Cook’s Pacific voyages of the 1760s and 1770s and subsequent waves of settlement;[viii] and, secondly, the Industrial Revolution, which brought technologies that facilitated the complete decimation and economic exploitation of the natural landscape, prompting the large-scale confiscation of Māori land.[ix]

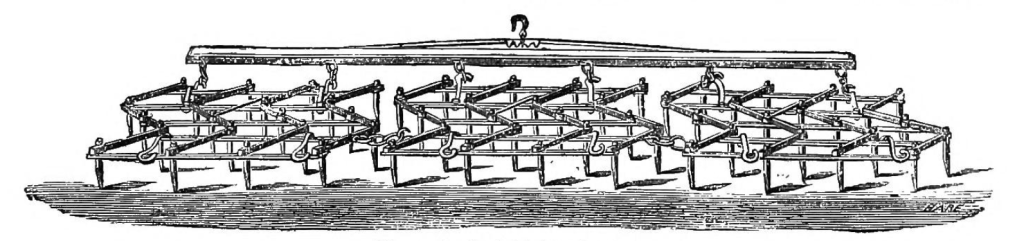

We are often reluctant to acknowledge these technologies as part of New Zealand’s colonial heritage. Many of them bring connotations of death and destruction: the iron harpoons and lances with which thousands of whales were slaughtered by on- and off-shore whalers; the specialised spears, spades, taps, and coils with which gum was extracted from kauri trees; the crosscut saws, timber jacks, tramways, and steam-powered sawmills with which countless acres of native forest were cleared; the sluices, explosives, hydraulic elevators, and bucket dredges with which bedrock and the riverbeds were stripped of minerals; the wool processors, refrigerated carriages, and dairy factories with which yet more native bush was cleared and more Māori land stolen to make way for agricultural holdings; the railroads, pipelines, telegraph lines, tunnels, and iron bridges with which Julius Vogel cut across the landscape, displacing thousands of Māori in the process; and, of course, the muskets and canons with which successive governors waged war against various iwi from the 1840s to the 1870s.[x]

*** Harrows, from Stephens' Book of the Farm, 1908

Harrows, from Stephens' Book of the Farm, 1908

It is no wonder that these technologies (with all their necrotic and imperialistic connotations) do not figure into Lilburn’s musical depictions of the New Zealand landscape – even though the landscape that Lilburn grew up with was so distinctly shaped by their deleterious effects.

Indeed, I would like to suggest that New Zealand music has long held an uneasy relationship with the spectre of technology. In particular, I suggest that New Zealand composers have long struggled to reconcile musical representations of technology with the pastoral conventions hailed by Lilburn as essential to our national musical aesthetic.

This technological discomfort, I argue, stems from our collective inability to acknowledge the extent to which the centuries-old machinery of colonialism has shaped our natural environment. It is rooted in cultural mythologies of an “untouched landscape” shared by many New Zealanders. Historian Miles Fairburn links these mythologies to the colonial notion of New Zealand as a “labourer’s paradise”: in the nineteenth century, colonists often boasted that New Zealand’s arcadian natural environment was so bounteous, so fertile, that very little human or technological intervention was required to harvest its fruits.[xi] This ideology was parodied in Samuel Butler’s famous 1872 satire of colonial New Zealand, Erewhon; or, Over the Range, which depicted an agrarian society who bans industrial technology for fear that machines will develop artificial intelligence and “supplant the race of man”.[xii]

These idyllic narratives can be seen today in government tourism campaigns (“100% Pure NZ”) or in Peter Jackson’s faux-agrarian “Hobbiton” set in Matamata. But they are also etched into the lonely landscapes of Rita Angus and Colin McCahon, echoed in the plays of Bruce Mason and the poems of James K. Baxter and Allen Curnow, and inscribed into the pastoral aesthetics of our so-called “national” musical style.[xiii]

***

L to R: Michael Norris, Alex Taylor, Celeste Oram, Eve de Castro-Robinson

L to R: Michael Norris, Alex Taylor, Celeste Oram, Eve de Castro-Robinson

In this short essay I want to highlight four recent compositions that seem to confront our collective discomfort with technology head on. For me, these four pieces offer a quiet antidote to Lilburn’s arcadian mythologising, honing in on key tensions that shape our cultural attitudes towards technology and the natural landscape.

I will analyse two works (by Michael Norris and Alex Taylor respectively) which, to my ears, draw attention to the technophobia attendant on our cultural preoccupation with the natural landscape. To me, these works underline (and even mock) our technological anxieties by presenting mechanical incursions on our soundscape as repulsive, monstrous, or even dangerous.

I will then turn my attention to works by Celeste Oram and Eve de Castro-Robinson which, conversely, highlight a degree of technophilia that arises, paradoxically, from myths of New Zealand as an ecological paradise. Just as the fable of New Zealand as an untouched arcadia stoked the expansion of colonial technological operations over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, so our cultural discomfort around technology belies a certain technophilic fixation. I suggest that Oram and de Castro-Robinson subtly draw attention to this technophilia by presenting a more nuanced history of the New Zealand landscape rooted in technological development.

Between these four pieces, a Janus-faced portrait of our nation’s technological discomfort emerges: on the one hand, the harrowed grimace of a Luddite and the gleeful smirk of a technomaniac on the other. And, collectively, they challenge the pastoralism, the utopianism, and the ecological revisionism on which Lilburn attempted to found his so-called “national style”.

One small note before I proceed: although I have framed New Zealand’s technological discomfort in decidedly colonial terms, these four works do not necessarily take an expressly decolonial stance towards the technologies they depict. Rather, these composers approach our cultural attitudes towards technology with a refreshing honesty: they do not deny its ongoing effect on our natural landscape; they do not deny the extent to which it has influenced our (colonial) cultural mythologies; and they do not deny the extent to which it has shaped our national history.

***

The technological frictions undergirding New Zealand’s arcadian view of its natural landscape are no more evident than in the so-called “Landscape Preludes”, a set of twelve virtuoso piano works (each by a different New Zealand composer) commissioned by pianist Stephen de Pledge in 2003. The “landscape” theme, by de Pledge’s own admission, was designed to bind the pieces together around a distinctly nationalistic aesthetic: in a 2008 interview, he stated that the theme was chosen to foster a “New Zealand feel” between the pieces, “an atmosphere that was different from something you’d get elsewhere in the world”.[xiv]

Some responded to this brief in a decidedly Lilburnian vein, conjuring forth pastoral depictions of New Zealand’s natural environment that seemingly embody the ecological ethos of Lilburn’s “living tradition”. Gareth Farr’s The Horizon from Owhiro Bay, for example, paints the Cook Strait skyline with a dazzling wash of modal colours not dissimilar to Lilburn’s own harmonic language.

Michael Norris’s contribution, however, takes a very different approach. Ambiguously titled Machine Noise, Norris’s prelude begins with the pianist alternating, robotically, between two notes at the outer extremes of the piano’s range. As the piece goes on, this mechanical oscillation is increasingly interrupted by abrupt and unexpected interjections – cluster chords, tremolos, and angular, virtuosic patterns that sweep up and down the range of the piano.

Before long, Norris’s “machine” comes to test the physical limits of the pianist’s body: there are moments in the piece that seem tortuous, laborious – even impossible – to perform, requiring the pianist to lurch up and down the keyboard, hitting cluster chord after cluster chord on their way. The “landscape” that Norris puts forward is thus one where machines threaten and impose upon the equilibrium of the body – an aesthetic at odds with the pastoral approach taken by many of the other contributors.

Although Norris intended the piece as a commentary on the human mind as a kind of biological mechanism,[xv] I would argue that his prelude goes a step further. Not only does it position machinery as a central facet of the New Zealand landscape (by dint of being a “landscape” prelude), it presents this technology as something sinister, uncomfortable, unpredictable, or even violent – both in its visible effect on the performer’s body and in the sonic effect of its erratic, dissonant musical language.

A similar approach is taken in Alex Taylor’s burlesques mécaniques, a series of miniatures commissioned by the New Zealand Trio in 2012. The miniatures are themed around various types of construction and/or household technology (“a spanner”, “scaffold”, “anglegrinder”, “tumbledry”, “chain” etc.) – garden-shed objects that give material form to our “number-eight-wire”/DIY mentality.

burlesques mécaniques is a kind of dance suite: the mechanism of each technology is parodied in each movement through a different style of dance (the turning of the spanner, for example, becomes a faltering habanera; the churning of the drag harrow becomes an off-kilter ragtime). And yet, like Norris, Taylor complicates the mechanical, repetitive rhythms of the dance topoi with an unnerving degree of musical complexity, to the extent that these dance forms seem skewed, obstructed, engorged, or distorted. To quote the composer himself: “conflicting rhythms dominate the surface, oscillating between insistent repetition and mad, angular flourishes.”[xvi] Thus, in burlesques méchaniques, an enduring tension between mechanical repetition and gestural complexity conspires to render grotesque the various technologies that it depicts.

For example, in the movement titled “anglegrinder” (ostensibly a tango), the cellist mimics the physical action of operating an angle grinder, pushing their bow harder and harder and lower and lower onto the string in short bursts. Meanwhile, the violin dispenses a gradually accelerating stream of (highly erratic, supercharged) musical material, seemingly imitating the sparks flying from the angle grinder as it cuts through metal. The tango rhythms can be heard in the piano; however, the right and left hands seem to be at odds with each other, as if they are playing two completely different tangos at the same time, and their respective lines are ultimately lost in the pulverising din of the angle-grinding strings.

It seems to me that Taylor gently problematises our cultural relationship with technology through a complex interplay of mockery and mimicry: the movements of these technologies are physically parodied while their mechanisms are cast as a sinister, offbeat choreography. New Zealand’s technological history is thus presented as a kind of monstrous sideshow, a terrifying carnival – equal parts alarmingly artificial and materially threatening – populated not with fortune tellers and sword swallowers, but with our everyday DIY objects.

burlesques mécaniques is like a mirror held up to our own technophobia: our own cultural anxieties around technology are reflected back onto the everyday technologies that shape our “number-eight-wire” mentality. In presenting these household technologies as freakish or outlandish, Taylor tacitly draws attention to their outsized role in configuring our physical and cultural landscapes.

***

A composer does not necessarily have to paint technology as grotesque or dangerous to highlight the cultural tensions surrounding New Zealand’s technological history. Eve de Castro-Robinson’s 2012 opera based on the life of influential kinetic artist Len Lye, for example, slowly teases apart various tensions between a sleepy Kiwi pastoralism and a cosmopolitan, hyper-energetic technophilia.

The opera opens on the beach in front of Lye’s childhood home at the Cape Campbell lighthouse. As the young Len experiments with the kinetic properties of a piece of driftwood, he is accompanied by an eerie soundscape evoking the natural sonorities of the stark Marlborough coast: a long, slow glissando that might be the howling of the wind; a strange trumpet call that could be the screeching of a gull; and a saxophone lick that recalls the waves lapping against the shoreline.

Over the course of the opera, it is as if Lye’s wild, coastal childhood is subsumed by the artist’s technological obsessions. As Lye’s artistic career progresses, more and more technology is introduced to the mise-en-scène: first, the artist’s experimental musical videos are projected onto the set; then, a miniature, light-up version of Lye’s Wind Wand is planted in the middle of the parterre; finally, in the opera’s breath-taking denouement, the distinctive sound of Lye’s kinetic sculpture A Flip and Two Twisters erupts throughout the theatre, accompanied by an equally clamorous percussion cadenza.[xvii] At this moment of technological saturation, the young Lye returns to the stage, holding his piece of driftwood high above his head, exalting in the machinic tumult that surrounds him.

In Len Lye: The Opera, there is always a tension between Lye’s rustic seaside upbringing and his high-tech aesthetic vision; it is this tension that propels Lye to pursue his artistic career overseas seeking an artistic establishment less invested in older (pastoral) models of landscape painting (and therefore less hostile to his unique form of avant-gardism).[xviii] And yet, paradoxically, de Castro-Robinson and librettist Roger Horrocks depict Lye’s interest in kinetic technology as emerging out of the artist’s childhood encounters with the ever-shifting New Zealand landscape. In doing so, they expose a latent technophilia underscoring myths of New Zealand pastoralism: the underlying tensions between technology and ecology in New Zealand’s cultural psyche only serve to stoke Lye’s technological imagination. The young Lye sees, in his piece of driftwood, both an emblem of a childhood paradise and the potential for technological development.

Celeste Oram has explored a similar convergence of pastoralism and technophilia in her so-called “reconstructions” of the work of New Zealand composer Vera Wyse Munro. Munro, a fictional figure cooked up by Oram herself, was purportedly a ham radio broadcaster and Morse-code improviser who transmitted her experimental compositions across the New Zealand airwaves from various homemade devices in the early twentieth century.

The New Zealand landscape was allegedly baked into the aesthetic fabric of Munro’s music. Oram describes Munro translating native bird calls into Morse code or broadcasting the sounds of the dawn chorus in her garden.[xix] Her ham radios used kauri trees as aerials and were bedecked with bird feathers. Her magnum opus, the Skywave Symphony, was literally built around a topographical map of the New Zealand landscape, experimenting with the way that its physical contours affected the sound of radio static.

Munro views New Zealand’s radiophonic networks as a function of the natural landscapes in which they operate. For Munro, the radio cannot be considered separately from the geographies that determine its broadcasting capacity. Thus, her New Zealand is not untouched by technology; rather, every hill and valley affects its technological development. Her music draws attention to the points of encounter between ecology and technology, celebrating the complexities, the messiness, of these encounters.

In positing the oeuvre of Vera Wyse Munro (and reimagining the history of New Zealand music in the process), Oram constructs a viable alternative to Lilburn’s pastoral national style – one in which the technophilia belying our obsession with the natural landscape is laid bare from the very start. Indeed, Oram’s Munro reconstructions, like de Castro-Robinson’s opera, are marked by a blunt honesty around the technological preoccupations that underpin our coveted pastoral mythologies. Through the figure of Munro, Oram shows that the history of our landscape cannot be disentangled from the histories of the technologies which shaped it and were shaped by it in turn.

***

Ironically, Lilburn’s own career would take a rather Munro-ish turn in the mid 1960s, as he began to develop a keen interest in electronic music and experimented with new technologies for manipulating the acoustical properties of sound. However, even as he retreated further into the newly-formed Victoria University of Wellington Electronic Music Studio, his aesthetic orientation remained wholly pastoral. Much of his electronic music, like his instrumental music before that, simply attempted to evoke the sounds of a natural, untouched landscape (see, for example, his 1979 Soundscape with Lake and River, his 1965 The Return, or his 1972 Three Inscapes).[xx] Even as Lilburn became increasingly reliant on technology to realise his artistic vision, he still came to promote an image of the New Zealand landscape in which technology was almost entirely absent, clinging on to myths of New Zealand as an unblemished arcadia.

Thus, Lilburn’s electronic works stand as emblems of both the technophilia and the technophobia that underscore our cultural attitudes towards New Zealand’s natural landscape. They simultaneously embrace the technological reconfiguration of the native environment while obscuring the extent to which technology has shaped this local ecology. They are our Erewhonian anxieties made sonorous.

[i] Quoted in Roger Horrocks, “Douglas Lilburn: Nationalism Now,” Journal of New Zealand Literature 29 (2011): 86.

[ii] Quoted in Robert Hoskins, “Editor’s Introduction,” in Douglas Lilburn: A Song of Islands, ed. Robert Hoskins (Wellington: Promethean Editions, 2015), v.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Rachael Selby, Pataka J. G. Moore and Malcolm Mulholland (eds.), Māori and the Environment: Kaitiaki (Wellington: Huia, 2010); Merata Kawharu, “Kaitiakitanga: A Maori Anthropological Perspective of the Maori Socio-Environmental Ethic of Resource Management,” The Journal of the Polynesian Society 109, no. 4 (December, 2000): 349-370.

[v] James Belich, Paradise Reforged: A History of the New Zealanders from the 1880s to the Year 2000 (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2001).

[vi] From Robin Hyde, “Prodigal Country,” (set by Lilburn in 1940), quoted in Peter Simpson, Bloomsbury South: The Arts in Christchurch, 1933-1953 (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2016), 112.

[vii] Indeed, Glenda Keam has already questioned whether the relationship between New Zealand composers and the natural landscape has produced a distinct national style, interrogating the extent to which some of the “spatial” harmonic effects found in New Zealand music can really be attributed to New Zealand’s wide, open spaces. See: Glenda Keam, “Exploring Notions of National Style: New Zealand Orchestral Music in the Late Twentieth Century” (PhD diss., University of Auckland, 2006).

[viii] John McAleer and Nigel Rigby (eds.), Captain Cook and the Pacific: Art, Exploration, and Empire (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017).

[ix] This environmental destruction was an inbuilt feature of the British colonial project. See: Tom Brooking and Eric Pawson, Seeds of Empire: The Environmental Transformation of New Zealand (London: L.B. Tauris, 2010).

[x] Emma L. Carroll, Jennifer A. Jackson, David Paton and Tim D. Smith, “Two Intense Decades of Nineteenth- Century Whaling Precipitated Rapid Decline of Right Whales around New Zealand and East Australia,” PloS One 9, no. 1 (April, 2014); Senka Božić-Vrbančić, “’Scars in the Ground’: Kauri Gum Stories,” in Oral History and Public Memories, ed. Paula Hamilton and Linda Shopes (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2008), 145-164; M. M. Roche, “The New Zealand Timber Economy, 1840–1935,” Journal of Historical Geography 16, no. 3 (1990): 295-313; T. J. Hearn, “Structural Change in the Otago Gold Mining Industry 1861-1923: The Matakanui Example,” New Zealand Geographer 46, no. 2 (October, 1990): 86-91; David Greasley and Les Oxley, “The Pastoral Boom, the Rural Land Market, and Long Swings in New Zealand Economic Growth, 1873-1939,” The Economic History Review 62, no. 2 (May, 2009): 324-349; Raewyn Dalziel, Julius Vogel: Business Politician (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1986); Vincent O’Malley, The New Zealand Wars: Ngā Pakanga o Aotearoa (Wellington: Bridget Williams Books, 2019).

[xi] Miles Fairburn, The Ideal Society and Its Enemies: The Foundations of Modern New Zealand Society, 1850–1900 (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1989). For more on utopianism and New Zealand colonial history, see: Lucy Sargisson and Lyman Tower Sargent, Living in Utopia: New Zealand’s Intentional Communities (London: Routledge, 2004).

[xii] Samuel Butler, Erewhon; or, Over the Range (London: Trübner and Co., 1872), 78.

[xiii] I am thinking here of Angus’s paintings of the sparse Canterbury landscape from the 1930s and 40s; McCahon’s North Otago Landscape series from 1967; Bruce Mason’s The End of the Golden Weather and his Healing Arch series; and Baxter’s “New Zealand” and Curnow’s “Landfall in Unknown Seas”.

[xiv] Stephen de Pledge, “The Landscape Preludes,” SOUNZ, April 29, 2008, YouTube video, 3:49, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zszeDdCz8ik.

[xv] Michael Norris, “Machine Noise,” SOUNZ, https://sounz.org.nz/works/16070.

[xvi] Alex Taylor, “burlesques méchaniques,” SOUNZ, https://sounz.org.nz/works/20902.

[xvii] This moment is strikingly captured on de Castro-Robinson’s 2012 album Releasing the Angel (Atoll Records), which includes a dance suite from the opera (played by the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra) as its final track.

[xviii] As Roger Horrocks describes in his biography of Len Lye: “The values promoted by art education mirrored those of the local art market. Buyers of paintings liked picturesque landscapes.” See: Roger Horrocks, Len Lye: A Biography (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2001), 24.

[xix] Celeste Oram, “Biography,” Vera Wyse Munro, https://verawysemunro.nz/Biography.

[xx] Michael Norris and John Young, “Half-Heard Sounds in the Summer Air: Electroacoustic Music in Wellington and the South Island of New Zealand,” Organised Sound 6, no. 1 (April, 2001): 21-28.